DMZ is © Brian Wood and Riccardo Burchielli. All rights reserved. Vertigo Comics, all related characters, their distinctive likenesses and related indicia are trademarks of DC Comics. The stories, incidents, and characters depicted within these pages are entirely fictional. All original website content is © Justin Giampaoli.

2.18.2015

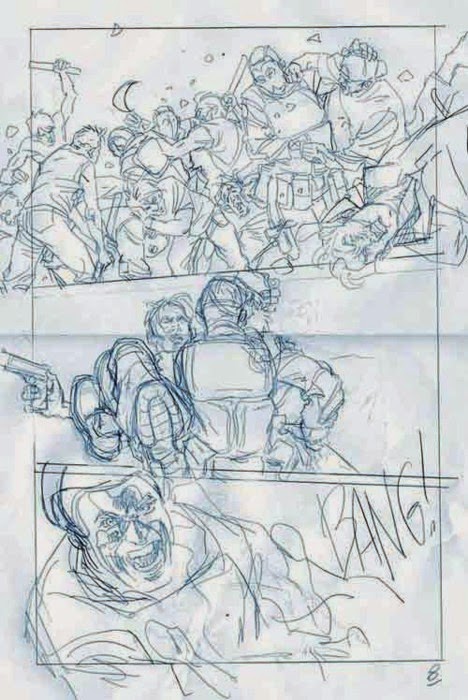

Volume 03: "Public Works," Interview w/ Writer Brian Wood

“Public Works” collects issues 13 through 17 and is essentially “the Trustwell arc.” It places Matthew Roth undercover within a work crew at Trustwell, which is ostensibly a government security and reconstruction contractor. Matty quickly learns the insidious truth about the nature of Trustwell and its relationship to the US Government. Public Works is a fascinating slice of the DMZ epic, which showcases the divergent perspectives and tactics of the FSA, USA, Liberty News, the United Nations, and Trustwell itself. Through Matty’s experiences with all of the intersecting dynamics in New York, we learn that the war is far from black and white. The USA is not purely a benevolent force trying to preserve the union, and the FSA isn’t simply a bunch of redneck militia advocating anarchy. Every side in the conflict possesses valid arguments, and the only certainty is that the inhabitants of the DMZ are caught in the turbulent crossfire. Everyone has an angle for sale; the PR war is just as high a priority as the ground war.

Brian, you play with allegory a lot in the political discourse of DMZ. Trustwell is not entirely dissimilar to, say, Blackwater or Halliburton. How much of the story content is inspired by the real world?

I think this one is rather “ripped from the headlines,” which is saying something in a series that is, you know, ripped from the headlines. I’m trying to think back to when this one was created, when I was writing these issues, and what was going on in the world… but I know there was dirty stuff being done by Blackwater for sure, and that’s absolutely where Trustwell came from. I’m fascinated by Blackwater… although now they rebranded as Xe, right? You know how to pronounce that? “Zee.” Love it.

At the time, I remember getting some of the first negative feedback over some of the choices I made in this story, specifically making the bad guys, the terrorist cell, Muslim. This decision came out of a back-and-forth with my editor (Will Dennis) because I had originally made them white guys. He called me on it, essentially, for making ALL bad guys in the book up to that point white, and perhaps I was playing it safe, or avoiding some potentially tricky decisions. His logic, which I agreed with, was that all these various ethnic groups who live in NYC didn’t just vanish once the war started. They’re still there, and just as apt to be up to no good as anyone else. And since Trustwell was using them as a front, that was another reason. They are obvious scapegoats because of their religion and skin color. But at the time, a lot of lefty types were loathe to let this sort of depiction go by unremarked, and I got a lot of emails from a lot of confused people.

Trustwell is basically a front company for war profiteering; do you think it’s your most politically perverse creation?

Maybe? Maybe Liberty News is, I dunno. I always regret not doing more with Trustwell, but like so many things in DMZ, too much to say and too little space and time. I’m clearly not done with the subject, though, since just recently in the DCU reboot book I was removed from, I had created a similar company called “Blackbell.” It’s still on the brain.

Was that for your aborted SUPERGIRL run? Or does the NDA prevent further discussion?

Ha. Christ, yeah. I’m under an NDA concerning certain details so I will only go so far as to say it was for an aborted DCU run. I hate that word, “aborted.” I’d say hired, worked for several months, and then fired, instead.

Matty witnesses a suicide bombing on his first day with Trustwell. I keep hearing that old adage about putting your protagonists where they’d least like to be to get the most dramatic tension. Are you conscious of these writing tools or is it truly an organic “follow your gut” process?

Most things I do are gut actions. That one in particular was rather bluntly done, since if I recall (I never have copies of the books handy!) the bombing took place at Ground Zero. It’s easy to do what you describe in DMZ because the whole arena is a place most characters don’t really want to be.

But I try not to follow those writer’s rules, at least not consciously. A lot of those rules are just simple common sense and so they happen organically whether or not the writer even knows the rules exist. Also, the structure of a monthly comic is not a natural one in the world of storytelling. DMZ is a 1550-page story, and on the face of it that’s fine. But it’s serialized, and designed to accommodate a huge second act, a potentially infinite and flexible second act that needs to work for 72 issues, or for 36 issues, or 24 issues had we gotten cancelled. It’s also a six-year ongoing thing and as such impossible to map out in detail and stick to religiously (for all but the most pious of writers). So a lot of the rules or standards for writing don’t always apply in comics. I try to think about that as I go.

From a craft standpoint, that’s interesting. The idea that you have to run parallel storytelling methodologies at any given moment, ie: you could run for 2-3 more years or be cancelled within months. Are you always aware of that, always creating mental back-up plans for various scenarios?

This is probably why there could be a lot left on the table idea-wise, threads and thoughts that never got explored. I’m actually going through this right now, setting up a new creator-owned book. It’s designed to be a 30 issue series, but the publisher, like all publishers (including DC) only commits to a certain amount of issues at first. Meaning, DC would not put it in writing that they will publish 72 issues of this weird book called DMZ in case, by issue 9, it was really tanking. They cover their bets and do it a year at a time.

So when you start, the prudent thing to do is to not get your hopes up too much, but at the same time it’s not like, with my new book, I can structure it so it can end at 12, 24, or 30. Not without screwing everything up, anyway. All you can really do is wrap it up the best you can in the time you have left, should the worst come to pass.

Street art and graffiti seem to be an indelible part of the DMZ landscape; here it’s “God Hates New York” tagged in the background. Do you feel this outlet gives people a voice that can’t be expressed otherwise?

In general, or in that one case? Not to sound like I’m passing the buck, but 99.9% of the time the graffiti is done by Riccardo, as an aspect of the art rather than me writing a script. I’m not sure I would know how to write it, to be honest.

It sounds like Riccardo has some flexibility with what he adds visually. Have you ever had to push back on him and have him remove/alter/enhance something that didn’t line up with the narrative?

Yeah, but minor stuff. Landmarks, facial expressions that are either too much or too little, zoom in, zoom out, stuff like that. But it’s not that common. If it happens more than once or twice in an arc, I’m surprised. He’s the co-creator on the book and he has a lot of freedom with the art.

How does Matty start to lose himself and his identity while he’s undercover at Trustwell?

The thing I keep reminding people, and reminding myself, is that Matty is not a journalist. He never was – he signed up to be an intern in a cubicle somewhere. He was dropped into the DMZ with zero experience and zero training. He PLAYS at being a journalist, and perhaps at times he is one, for some fleeting moments. Maybe at the end of the series he can look back and say, yeah, that was the point where I became one for real. But at the time of Public Works? Not even close. He’s in way over his head, and probably lost himself right away.

The water torture scene is particularly disturbing. How do you begin writing that? Did you research any of the Guantanamo Bay incidents, or is this all intuitive?

It was steeped in the culture of the time, in the news, and on people’s lips. No research was really required for that, sadly. It was pointed out to me well after the fact that what I did was essentially recreate a similar scene from V FOR VENDETTA, which I suppose is true, but certainly not deliberately.

Why is the character of Amina important to the DMZ narrative?

Amina is a total tragedy. She is a living, breathing example of Matty fucking up. Not that she wasn’t tragic before that, or wouldn’t have come to a tragic end if Matty hadn’t decided to intervene. But whatever good came out of the Public Works story – and Matty did do good in terms of exposing Trustwell, earning back some goodwill from Liberty, paving the way for his extraordinary access in “Friendly Fire – whatever good will forever be tainted by the fact he messed up with Amina. I check back in with her a few times, and not until her final chapter in Volume 10 does she get back on track with her life. What’s all the more tragic is that Matty has no idea how he screwed her life up.

But Zee knows, right? If Zee is a physical manifestation of the city, then the city sees all!

I think Zee probably knows more than anyone thinks she knows.

The Secretary General of the United Nations is killed in an attack on his convoy. The scene reminded me that the “action scenes” in DMZ are never portrayed as fun popcorn entertainment. They’re never noble or glamorous, just unexpected and scary as hell. How do you maintain that realism?

That’s another ripped from the headlines thing. That scene came about after reading an article about the attack on the UN headquarters in Iraq in 2003 that prompted the organization to leave the country.

When I was coming up in law enforcement, I had a mentor that told me the profession was “99% boredom and procedure, followed by 1% of unpredictability and sheer terror.” That scene made me think of that line.

I’m sure there’s a comment to be made there about the overuse of tasers, somewhere, if only 1% of the time do things get heavy.

On this reading of the entire series, it’s obvious that the FSA is ubiquitous. They pop up everywhere at the most interesting moments; they’re even undercover at Trustwell. Is everyone underestimating the FSA and their reach?

The FSA was always more of a concept than a formal army, and while they did accomplish a lot as an army, they never had much of a leadership or a stated goal. And so they are able to be everywhere… the FSA can exist in the individual, and that’s a scary concept. At the start of the series, a lot of readers were eager to draw the lines and find comparisons, and the FSA were tagged as the “good guys,” the ones that I, the writer, was politically in line with, the lefties, the justice-seekers. But from the get-go, I never put them in that position. They’re horrible, just like the U.S. shock troops are horrible, just like Liberty and Trustwell are horrible, just like Parco and Matty did all this horrible stuff. There’s no good guy/bad guy divide to be found here. Not a simple one, anyway.

Exactly. Anyone and everyone has the capacity to do “bad” under the right set of psychological stressors. The FSA is scary because of their stealth, it’s that idea of asymmetrical warfare you play with that permeates the whole thing. How do you fight the enemy if they can’t be identified? If they’re among you? If they’re actually you?

I’m sure it’s beyond scary and frustrating for the people who try to fight asymmetry with conventional tactics. I remember a really awkward phase of the Iraq invasion where Rumsfeld or someone just like him was complaining about how all these insurgents do unfair things like not wear uniforms and hide. The implication being that he wished they would wear bright colors and line up so they could be shot more easily.

Ha, good ol’ “Rummy.” It’s all about point of view, right? There were some people from your part of the country that used very similar hit-and-run guerrilla tactics to overthrow the British Crown in the Revolutionary War. I don’t know if it was Howard Zinn or where I read it, but someone made the point that from the perspective of the British, an event like the Boston Tea Party wasn’t some birth-of-a-nation incident, but a terrorist act by a local insurgent cell.

Is DMZ a title like NORTHLANDERS that requires large amounts of research? Have you done research into Civil Wars around the world, re-read the Gettysburg Address, anything like that?

I would say it was DMZ that started me on my research kick, my desire to write books that require that level of work on my part to get the details right. I read a ton of books for DMZ, not so much the Civil War, but a good chunk of the plethora of books that sprang up dealing with both Iraq wars, as well as some earlier ones on Bosnia and the Soviet war in Afghanistan. Like with NORTHLANDERS, I front-loaded my brain to the point where I literally could not bear to read another word, and that research has carried me through.

I might be at the end of that, though. I might have reached my limit. I wrote this crime thriller pitch that’s set in Italy during the time of da Vinci, and I knew I couldn’t handle it. The Church, the Medici, the Masons… all in the story, all requiring more research than I could bear to take on right now. It’s not just a lot of work; it’s a lot of pressure since people actively look for mistakes.

End Transmission

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment